You know what they call Dungeons & Dragons in Paris?

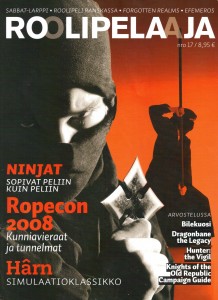

This is the English original version of my article on the French tabletop rpg scene, published in Finnish rpg magazine Roolipelaaja a few years ago. It is a bit dated, but still useful for scholars and if you speak Finnish or want to see the pictures, scans can be downloaded here. Special thanks to Juhana Pettersson for requesting the article in the first place and authorizing its sharing.

This is the English original version of my article on the French tabletop rpg scene, published in Finnish rpg magazine Roolipelaaja a few years ago. It is a bit dated, but still useful for scholars and if you speak Finnish or want to see the pictures, scans can be downloaded here. Special thanks to Juhana Pettersson for requesting the article in the first place and authorizing its sharing.

—

You know what they call Dungeons & Dragons in Paris?

The stereotypical rôliste (French for roolipelaaja) is a middle-class Caucasian male with some sort of college education who drinks soda and eats junk food while playing the exact same D&D that can be found throughout the world. That being said, there are indeed a few “little differences” with other western countries.

Excuse my French

The French speak French, and they’re damn proud of it. For example, all American films and series are dubbed on TV, fostering a rather limited English proficiency. As a result, the first rôlistes in the late ‘70s were students from fancy universities who had already been exposed to obscure games with English rules like wargames and Diplomacy. The few that got their hands on D&D manuals during trips abroad usually spread them through photocopies. So from the very beginning, French game speak was peppered with words like XP or DM. Those are still in use today, especially among older players. However, “role playing game” was soon translated as jeu de rôle, and abbreviated as jdr (RPG designates video games).

The rôliste population did grow since the ‘70s, but never benefited from a proper census. Once estimated at 400’000, it is most likely under 50’000 active gamers, which still ensures the commercial viability of translating successful English-language RPG lines. Translated books are often longer than the originals: first because it takes more words to say the same thing in French than in English, but also because they contain more gaming material. For example, each French Way of the… supplements for Legend of the 5 rings included a scenario. And in case France itself is part of a game setting, importers will try to negotiate the rights to create a specific country supplement such as for the World of Darkness, Hawkmoon or Shadowrunlines. Looks are also very important: if the American art is considered sub-par, publishers will replace it. In extreme cases such as photos of action dolls, the book will be entirely redone, cover to cover. To finish with imported games, the only non-English RPG to have made a lasting impression in France was German… and that was back in the ‘80s.

Au début des années 80

The first French-language RPG books hit the stores in 1983. The translation of D&D’s red box of course, but also two French creations, with fantasy (L’ultime épreuve) and Celtic settings (Légendes). At the same time, translated choose-your-own-adventure books were a huge hit in mainstream bookstores. Their importer translated Das Schwarze Auge and published its rulebooks with the exact same layout as adventure books. While it did feel like a bait and switch for most unsuspecting readers, many loved the concept of playing as a group and joined the ranks of the rôlistes. Another mainstream publishing company released two RPGs, including the first French space opera, Empire Galactique. These big firms didn’t really know how to market such strange books, sales went down and RPGs weren’t seen in standard bookstores for many years. Meanwhile, far from established distribution networks, many rôlistes were already bored with the usual American dungeon-crawling and decided to publish their own games.

L’exception culturelle

When asked about what differences there were between the French and American RPG crowds, French iconoclast RPG creator Croc answered: “One has a brain, the other doesn’t”. Indeed, the French see themselves as smarter or more “cultured” than Americans and pride themselves on preserving their national creations from Yankee invasion. This did not stop McDonald’s from being the #1 restaurant company in France, and D&D the best selling RPG. French games do deviate from the American RPG norm, but more so in style than substance. In movie equivalents, think more Luc Besson and Jean-Pierre Jeunet than Jean-Luc Godard. So what did the résistance come up with in the ‘80s? As a reaction against the number crunching, the first horror game, Maléfices, had a very simple system and relied on traditional French folklore rather than on Lovecraftian tentacles. Hurlements insisted so much on its historical mystery mood that players weren’t allowed to see their -minimalist- character sheets. Crunchier fantasy systems benefitted from settings with humorous and poetic twists. The world of Rêve de Dragon is a collection of dragons’ dreams, and Animonde characters are essentially hippies with pets for equipment. Not being led by seasoned businessmen, many of these fledgling game publishers disappeared within a few years. Some games kept a cult following, and some were later republished by more stable companies.

A golden age?

The ‘90s were a somewhat paradoxical time for French RPGs, with both unprecedented commercial growth and very bad press. In 1990, a Jewish cemetery in the town of Carpentras was profaned and rôlistes accused of doing it as part of a roleplaying game. Police investigations later proved that the culprits were actually neonazi skinheads, but the PR damage was done. In the following years, tragic events like teen suicides or assaults were also blamed on RPGs. Again, investigations showed that these teens were unstable, depressed, suffering from their parents’ divorce or from being put in a boarding school, but RPGs made fine scapegoats. Several prime-time TV shows ran interviews of concerned psychiatrists warning parents against manipulative game masters. As a result, several cons got canceled, high-school gaming clubs forbidden by school principals etc. This prompted the creation of the Fédération Française de Jeux de Rôle, to provide journalists and politicians with an official interlocutor. But even to this day, most rôlistes don’t care much about organizing their hobby and mainly care about playing with their own gaming group.

Livin’ large

On the business side, Asmodée and Multisim were the two main publishers of original French games in the 90s. The former was seen as a producer of edgy action games, the latter as more esoteric and intellectual. Both companies had several full-time employees, efficient distribution networks and access to specialized magazines to advertise their products. New RPG lines were released regularly, with serious art direction that led to much more professional looks than in the 80s, as well as spin-off products like novels or trading card games. Internationally limited to the French-speaking parts of Belgium, Switzerland and Canada, companies also tried to reach Anglophone markets. Multisim’s Nephilim and Agone made it to the US, and Asmodée’s INS/MV (see box) traveled far and wide. Its German, Spanish and Polish editions were rather faithful to the original, but In Nomine, its US adaptation, was completely sanitized to accommodate the more conservative American tastes. Likewise, the latest French export Qin (see box) lost its God of Sodomy when crossing the Atlantic.

Balkanization

A few years into the 21st century, sales start to lag. Some blamed the lack of customers on bad press, the absence of a good introductory RPG, competition from trading card games and MMORPGs or aging gamers too busy with the wife and kids. Another factor could be that rôlistes just don’t need to buy that many manuals anyway, and can keep going with their old Player Handbook for years, writing their own scenarios. Various companies went bankrupt and all RPG magazines disappeared. Key journalists and game writers of the 1990s moved on to greener pastures, usually in the computer game industry or writing novels and comics. Even profitable companies like Asmodée, eventually decided to stop creating RPGs, concentrating on more lucrative products like boardgames. With most unifying factors gone, conventions and the internet became to only way to keep some sense of community. Sites were built around specific games, or to provide centralized resources like scenarios etc. The number one site in French RPG scene, www.roliste.org, actually started out as a madman’s dream: to reference every single RPG book ever published in the world. It is now a key portal, its neutral and thorough spec sheets are complemented with reviews, links, industry news and grants the only French RPG award, the GROG d’Or.

Renaissance

While major publishers used to be located in Paris, the internet enabled game creation by groups of francophone writers and artists scattered around the world. Free desktop publishing software, the emergence of the PDF format and print-on-demand services like Lulu.com enables more small games to come out, blurring the line between amateurs and professionals. Some writers experiment with Greg Stolze’s ransom model, while others work for free to ensure their game gets printed the way they want. Indeed, as rôlistes are used to hardback, lavishly illustrated rulebooks, traditional printing is still considered the gold standard. It does come at a cost: smaller audiences mean that a core book selling a few thousand copies is considered a success, and print runs for supplements rarely go above one thousand.

As always, the mass market is dominated by D&D, and many hope that 4th edition will bring young blood to the hobby by tapping the WoW crowd.

So how do they call D&D in Paris? Donjons & Dragons. In true “quarter pounder with cheese” fashion, a donjon is actually a very high tower, not some underground prison. I guess, we’ll plead « exception culturelle» again.

==BOX: 5 subjective picks ===

Qin, les Royaumes Combattants (7e Cercle, 2005): ancient China wuxia action. A hit due to a subtle combination of amazing art, sheer kung fu fun and an attention to historical accuracy that differentiated it from Feng Shui or even Legends of the 5 Rings (Available in English as Qin, The Warring States).

COPS(Asmodée, 2003): police officers in a near-future independent California. Not quite cyberpunk, the very rich product line was probably the first to be designed with an overarching storyline in mind, divided in seasons like a TV series (in French only).

In Nomine Satanis / Magna Veritas (Asmodée, 1989): angels and demons in modern day France, full of dark humor, anti-clericalism, pop culture, extreme politics and super powers. INS/MV was written before Neil Gaiman & Terry Pratchett’s Good Omens came out, but was later heavily influenced by it (Sort of available in English as In Nomine).

Final Frontier (John Doe, 2006): a tongue-in-cheek approach to Star Trek-like sci-fi series, with rules that really aim at simulating their soap opera elements. Fans have adapted the system to play in more serious settings like BattleStar Galactica. Part of a line of shorter, self-contained RPGs for gamers with less time to spend on complex settings (in French only).

René, le jeu de rôle romantique (Philippe Tromeur, 2000): a game parodying 19th century romantic literature, mostly available online. Each scenario is called a tragedy, PCs spend their days moaning while their loose clothing flaps in the wind, secretly falling in love with their sisters and committing suicide on Brittany cliffs (available in English as Wuthering Heights Roleplay).

===END BOX===

===BOX: What about LARP?===

Jeu de rôle grandeur nature (lit. “life-size roleplaying”, usually abbreviated as GN) has been around since the ‘80s. GNistes (larpers) are a minority compared to rôlistes, and constitute a somewhat different demographic. Because of the higher cost of entry, the average GNiste is usually older and more often a professional than a student. He’s also much more often a she, with a good third of female larpers. The average game is medieval fantasy with latex swords (France has no shortage of castles and forests) but more exotic historical or sci-fi settings are also available. There are no enormous battles like The Gathering or Drachenfest and freeforms are unheard of. One-shot murder mystery games are quite popular, as their short duration and ease of organizing matches an aging, child-rearing population. In terms of gameplay, the French larping style is somewhere halfway between barely costumed, number-yelling American boffers and the experimental/immersionist Finnish larp scene, possibly closer to what the Swedes do.

Most French larpers don’t care about larp theory and analysis, so Solmukhota-style conventions don’t really exist. The closest thing is les GNiales, a daytime con where organizers meet and share on pratical topics from legal aspects to plot writing. At night is La nuit des huis clos, where 15 small games are run at the same time.

===END BOX===

Related

4 Responses to You know what they call Dungeons & Dragons in Paris?

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

No Trackbacks.

Tags

2013 afroasiatik burlesque conquest of mythodea convention critique défi XVIIIème english français french french larp gn gniales gnidee hip-hop huis clos jdr jeu de rôle jeu de rôle grandeur nature knudepunkt knutepunkt kung-fu lacepunk larp le four fantastique murder party mythodea nodal point nordic larp old news orc'idée podcast radio roliste rap review roliste sk2012 solmukohta steampunk stim suisse swiss larp switzerland thomas b. XVIIIèmePeeps be commentin’

- GEESAMAN8 on Deux GN avec du Star Wars dedans, un marathon et de l’oralité

- Steampunk Props Part 3: Gun, Smoke Rings video, Bubbles, a Chandelier and Art by Latranis - Thomas B. on Cheese-eating larper monkeys: the GNiales 2011 recap

- I'm a size 47 media whore and here's what sells online - Thomas B. on And they piss like I cry over unfaithful women

Search

[…] should go fine and as a special, I want to make some advertisement for fellow RPG blogger Thomas Be’s text on French role-playing games. Two cool facts before you should leave my blog: 1. The post has been published first in a Finnish […]

[…] Thomas Be a mis un article en anglais sur son blog pour présenter aux gens d’ailleurs le jdr …. […]

[…] a final comment on keywords, my article on rpgs in France attracted of lot of people looking for S&M dungeons in Paris and my piece on Jacques Brel seems […]

[…] side than the experimental one, sadly). French roleplaying is still a cottage industry, but also very stylistically diverse and is way past its witch hunt days. Demographics wise, not much as changed but larping has a […]