Afroasiatik – a kung-fu hip-hop larp – recap part 1

Warning: long posts ahead. Read the short version here.

Afroasiatik was a French-Swiss larp run in the zen garden of Aigle, Switzerland on Sunday 25th August 2013 with pre-game workshops on Saturday 24th August in Lausanne. Both Aigle and Lausanne are located in Romandie, the western, French-speaking part of Switzerland.

View on the Swiss mountains from the garden (Photo © Valérie Bauwens)

Part 1: the original reason for the game, a history of French hip-hop and its Asian influences

Part 2: how inspiration sources were used to build a game world that featured kimono-wearing rappers in a European zen garden

Part 3: the performance aspect of the larp and what worked, what didn’t

What “French-Swiss larp” means for Afroasiatik :

- I came up with the original idea and wrote the main documents. I am French, born and raised in Paris, France, and lived for four years in San Francisco, USA. My hip-hop education was made in Paris, so Afroasiatik focused on French hip-hop, not American or Swiss hip-hop. I have been living and larping in Switzerland for nearly ten years, so my blog covers more Swiss larp than French larp. For more on the latter, try Electro-Larp.com

- Shub NigguBarth, the co-author who wrote half the characters and co-organized the game, is French and lives in France. We were helped by Lucien, a Swiss member of Le Four Fantastique, my informal larp group, for some of the characters.

- The photographer, Valérie Bauwens, is Belgian I think, additional pics and videos are by Oliver V., who is Swiss

- Half the players lived in Romandie, the other half traveled from France, as far as Bordeaux, for the game. I don’t know their actual nationality or ethnicity.

So yeah, French-Swiss.

Larp and hip-hop, WTF?

Afroasiatik was based on French hip-hop, wuxia Hong-Kong action movies, Japanese anime and a 25-year old French tradition of mixing all three elements (yes, keep reading). I knew of French tabletop and live-action roleplaying games inspired by A Chinese Ghost Story movies, and by shōjo manga, but to my knowledge there had never been hip-hop larps.

I started both actively listening to French rap and playing tabletop RPGs in 1989, and quickly realized that the demographics were rather different. Some of my friends liked both, but overall these hobbies seemed to appeal to different kinds of people. I thought it was pity as I like mixing social groups, but throughout my teens, I got used to being the only skinny guy with long, straight hair and thick glasses at hip-hop concerts. There were plenty of other white people so race did not make me stand out. But my hairstyle -neither short-cropped nor dreadlocked- and overall looks definitely did. Conversely, while I fitted visually in gaming conventions, I was often the only guy listening to hip-hop when all the other GMs used metal or the Conan the Barbarian original soundtrack as mood music. Also, unlike the hip-hop scene, the gaming scene definitely lacked ethnic and economic diversity. Gamers where mostly white, middle-class and in -or on on their way to- college. However, in early 1990s France, hip-hop and roleplaying did have a few things in common :

- they were overwhelmingly male, meaning it was easier to date outside of both groups and none of my girlfriends at the time shared my hobbies

- they involved a lot of creating personas out of nothing and a lot of storytelling, both in and out of character (more on this later)

- they were either ignored or frowned upon by French society in general, and the media kept misrepresenting them (to simplify: hip-hop fans were ridiculous, illiterate and violent and roleplaying fans were suicidal Satan-worshipping Nazis)

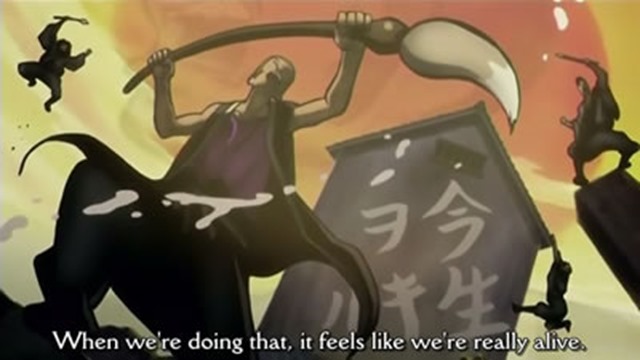

Mugen from Samurai Champloo

Fast forward 2012: the situation has evolved quite a bit

I have expatriated twice, am in my thirties, with a serious job, a Swiss green card and a receding hairline. French hip-hop is mainstream, spans a huge spectrum from experimental to gangsta and has been a million-dollar business for more than 15 years (more due to the gangsta side than the experimental one, sadly). French roleplaying is still a cottage industry, but also very stylistically diverse and is way past its witch hunt days. Demographics wise, not much as changed. larping has a rather even gender balance and gets regular positive reviews in the media, both in France and Switzerland. I even have a Swiss larping girlfriend who gets me a Samurai Champloo DVD set as gift (opening credits, wikipedia). Seeing this mix of hip-hop and Edo-period Japanese culture re-ignites my old dream to merge hip-hop and roleplaying. If larpers are into Asian elements, as shown by the success of the Chinese Ghost Story and shōjo games, maybe I can try a Samurai Champloo approach? Plus I spend my days listening to a new generation of French instrumental hip-hop beatmakers. They keep using Asian samples, related or not to their parents’ origins (Tha Trickaz, Onra, Chinese Man). These tracks are perfect for an Asian atmosphere and are easier than mainstream French rap on a newbie ear due to their absence of French vocal tracks. So I have a soundtrack, and an anime gateway drug. All I need is a game site and a few larpers, open-minded or crazy enough to try it.

Graffiti artists in Samurai Champloo

Site-based game design

Since my Shadowrun larp, I have been very picky about game sites and am in constant “location scout” mode. Through luck and good timing, I landed a whole movie theater for Technocculte and a whole boat for La croisière s’accuse (Loathe Boat), so I wanted something just as immersive this time. The same girlfriend pointed me towards the zen garden in Aigle. The site had fantastic elements, but also meant it would not be usable for a true Samurai Champloo larp.

There were visible modern elements, from a huge warehouse store next door to power lines and factory chimneys in the distance, and a freeway that could be heard and seen from some parts of the site. So by the standards of 360° illusion, the larp would need to be set in the modern day.

The garden was full of fragile elements, from flowers to statues, and lacked large open areas, meaning there couldn’t be any large group scenes and movement would have to be very restricted. There would be no running and fighting like in the Shadowrun game for example. Any Samurai Champloo-style battles would need to be ritualized duels and restricted to small locations. I did not want a stray latex katana to damage a bonsai.

The most important issue was that the garden was completely syncretic and multicultural, mixing elements from all over Asia with little apparent logic. Meaning it was just not credible “as is” for a serious Japanese game, whether Edo-period or not. Therefore, the game would need to incorporate a similar mix of Asian influences, and be much less serious, less in-depth than intended. Luckily, this also meant that the garden owners could potentially be open-minded enough to welcome an extra culture (or two) in the mix. I remembered that Onra was already mixing Vietnamese and Chinese samples, but I could quote way more famous French artists with a 25-years record of shamelessly mixing cultures.

The largest clear, flat surface in the garden that was protected from rain (Photo © Valérie Bauwens)

Back to the old school

French hip-hop is old. Obviously not as old as American hip-hop, but more than 30 years old. In the late 70s-early 80s, a few lucky French souls traveled to the USA and stumbled upon artists like Grandmaster Flash, Kool Herc, The Sugarhill Gang, Fab 5 Freddy, Rock Steady Crew etc. They grabbed whatever funk records they could in record stores. Clerks gave them strange looks while pointing them to the rock section (like future DJ Dee Nasty in San Francisco). They took lots of pictures of dancers and MCs (like future journalist Sophie Bramly in NYC) and came back to France with starry eyes. They made a few converts but records were hard to obtain.

Some French producers also noted the new trend, and in 1983 the same French duo that created the Village People tried to repeat the cash wonder by producing Break Machine. I remember dancing to Street Dance as kid, trying to copy the moves. As this was #1 in Norway and Sweden, maybe some in the Knutepunkt crowd also danced to it, who knows.

Other producers worked with French artists: the first time most French people heard rapping in their own language was in 1981, when pop duo Chagrin d’amour released their hit single Chacun fait (c’qui lui plait) (Everybody does as they please). Unlike Blondie’s contemporary Rapture, the band did not not namecheck any rappers, did not identify as hip-hop and did not even use the word. But it’s funny that the very first record featuring rapping in French is a jaded French bourgeois narrative dealing with nightlife, prostitution, champagne and problems with the police.

CHAGRIN D’AMOUR- Chacun Fait par sofresh305

A more comprehensive view of hip-hop culture reached the French mainstream in 1984 with the TV youth program H.I.P. H.O.P.. It was hosted by Sidney, originally a funk DJ, one of the first hip-hop dancers and rappers in France and the first black host on French national TV. The show’s artistic director was none other than Sophie Bramly, who had the US connections to bring artists such as The Sugarhill Gang, Kurtis Blow, Afrika Bambaataa, Herbie Hancock, etc to the show. The show featured rapping in both languages, graffiti and some turntablism (I grew up thinking Herbie Hancock was a hip-hop artist, not a jazzman, because of Rockit). However it remains most famous for its dance battles. Kids who had practiced their best moves, in their apartments or on cardboard/linoleum sheets in the street, would come and showcase their talent weekly on TF1, the most watched national TV channel.

H.I.P. H.O.P. lasted one year, making the average Frenchperson think that hip-hop was a fad that came and went. Sophie Bramly would later go on to design and host a show called Yo! MTV Raps on MTV Europe, one year before the American version of the show was created. Both shows remained active for several years until the European one was cancelled to save costs.

1984 was also the year of the first two French larp events and the release year of the first French hip-hop record, Paname City Rappin’ by Dee Nasty. It was heavily inspired by Afrika Bambaataa, who made him Grand Master of Zulu Nation in France. While Dee Nasty did rap in his album, he quickly focused on DJing, as seen in this old TV report with Destroy Man and Jhonygo, rappers on the second French hip-hop record in 1987. Yes, the Grand Master of Zulu Nation in France is the guy in the middle.

OK, enough bragging about the “French people have been doing this shit for a long time”, let’s add Asian elements to the mix with the band IAM, the key inspiration for Afroasiatik.

L’alliance des poètes afro-asiatiques

While Parisians relied on trips to the USA to get their fresh hip-hop fix, people from the south of France were receiving records at home thanks to American soldiers whose ships would stop in Marseille. This created an independent hip-hop culture in the region, with different US influences. E.g. if the northern band Suprême NTM sounded like Public Enemy in the beginning, the southern band IAM was more influenced by Erik B. & Rakim.

Iam: “Red Black And Green” par Petidragon

The IAM acronym has many meanings, first and foremost Imperial Asiatic Men. In France the word “Asiatic” or rather “Asiatique” does not have the dated and negative connotation it has in English, it is the same meaning as “Asian”. All the members of the band are French nationals, with origins in Algeria, France (mainland and Réunion), Italy, Senegal and Madagascar. None of the members identify as Asian in the US racial meaning of the word.

IAM obviously also means “I am”, but also “Invasion Arriving from Mars, “Independent Autonomist Marseillais”. Mars is their nickname for Marseille. They use the planet reference to differentiate themselves from the rest of France, proudly representing themselves as aliens. They often rap against centralization of French resources around in Paris and highlight Marseille’s rich past as a trading post in the Mediterranean since ancient times.

IAM does have traditional French rap lyrics on politics (against racism, corruption), history (Italian immigration, the slave trade), ego-tripping, humor and social commentary. However their originality was to develop a unique lexicon, combining both Pan-Africanist elements reminiscent of Cheikh Anta Diop, ubiquitous references to ancient Egypt (some members are called Akhenaton, Imhotep, Kheops and Kephren), science and science fiction (namechecking Mendeleev’s periodic table, writing entire songs about serving the Dark Side of the Force), religion (from Islam to Daoism) and Asia.

A good example is from one of their oldest songs, IAM Concept. Most of the poetry is lost in translation, if you speak French check out the original.

“I” for Imperial, indivisible and immutable

Impulsive and unchangeable

Like the Chinese Empire and the dynasties

of Upper and Lower Egypt and the God of Akhanjati

Aton Almighty, A as in Asiatic

First letter of the alphabet for Africa the motherland

Halfway through the taolu, I hit the pao

Don’t try to struggle or you will stay K.O.

M all my brothers [the letter M sounds like “love” in French], M as in Men meaning

Humans, with equal rights, the same and to sum up

Make the tiara of Queen Unity shine

Shall I say IAM

The name of the larp, Afroasiatik, actually comes from a line in this song “Inutile de lutter devant les poètes de l’Alliance afro-asiatique” (It is useless to fight against poets of the Afro-Asian Alliance).

Asian references started even before IAM, when the band was called B Boys Stance in 1988, with the arrival of rapper Shurik’n Chang-Ti. Born Geoffroy Mussard, in the small town of Miramas near Marseille, combining Japanese and Chinese references in one name was never an issue for this Frenchman with origins in Madagascar and Réunion. He was a kung-fu champion and aikido practitioner, seeing his rapping and martial arts practice as parts of the same path towards personal discipline. As a reminder to American hip-hop fans, all this happened several years before Fu-Schnickens and Wu-Tang Clan.

IAM made it big in 1994 with Je danse le mia, a nostalgic song about 1980s nightclubs in Marseille from their 1993 Egyptian-themed album Ombre est Lumière (Shadow is Light). Instead of going further into the nostalgic 1980s vein, they kept their political lyrics. In 1995, they showed their anime awareness by sampling from the Akira OST for their track La 25e image (the 25th image, about the dangers of violence in the media). They further increased their use of Asian aesthetics in 1997 with L’école du micro d’argent (School of the silver mic). To this day, it still considered their best album. Its graphics all revolved around a pop mashup of martial Asian imagery, from samurais on the cover to kung-fu schematics inside the booklet. The esthetics of Afroasiatik were highly influenced by this album, which provided the perfect mirror image for Samurai Champloo, with the same random mix of cultures found in the zen garden. The lyrics of the eponymous song are mainly about egotripping, defeating their enemies, using martial arts vocabulary.

IAM made it big in 1994 with Je danse le mia, a nostalgic song about 1980s nightclubs in Marseille from their 1993 Egyptian-themed album Ombre est Lumière (Shadow is Light). Instead of going further into the nostalgic 1980s vein, they kept their political lyrics. In 1995, they showed their anime awareness by sampling from the Akira OST for their track La 25e image (the 25th image, about the dangers of violence in the media). They further increased their use of Asian aesthetics in 1997 with L’école du micro d’argent (School of the silver mic). To this day, it still considered their best album. Its graphics all revolved around a pop mashup of martial Asian imagery, from samurais on the cover to kung-fu schematics inside the booklet. The esthetics of Afroasiatik were highly influenced by this album, which provided the perfect mirror image for Samurai Champloo, with the same random mix of cultures found in the zen garden. The lyrics of the eponymous song are mainly about egotripping, defeating their enemies, using martial arts vocabulary.

IAM l’Ecole du Micro d’Argent Clip inedit 1997 par johnrain

Due to very fitting lyrics, the organizers of Afroasiatik rapped a part of another martial arts egotripping song from that album, Quand tu allais on revenait (when you were going there we were already coming back). In the same vein, a track from Shurik’n’s solo album Où je vis (where I live) was used for one of the dance performances: Comme un samourai (like a samurai). Its lyrics are much more grim than the previous two tracks, and deal with the toughness of life growing up in poor neighborhoods and how you need to be like a samurai (a year before the movie Ghost Dog).

In 2000, Shurik’n released an album called La Garde (The Guard) with his brother Faf Larage. While Shurik’n is influenced by Asia, Faf Larage was more influence by European fantasy, dropping references to Michael Moorcock’s Stormbringer and adopting a European knight look for the album cover and videos.

La garde meurt mais ne se rend pas! (The Guard dies but does not surrender!), is a Napoleonic quote and you’re about to watch two guys in armor rapping in French. Welcome to my world.

La légende des deux lames (The legend of two blades), same as above, but going more outdoors.

I hope the above was useful to get a better, albeit very limited, idea of old-school french hip-hop, the extent of cultural appropriation in it and how it influenced Afroasiatik.

In the next part: influences more recent than IAM, rationale for developing the game world, hip-hop themes etc.

Related

5 Responses to Afroasiatik – a kung-fu hip-hop larp – recap part 1

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

No Trackbacks.

Tags

2013 afroasiatik burlesque conquest of mythodea convention critique défi XVIIIème english français french french larp gn gniales gnidee hip-hop huis clos jdr jeu de rôle jeu de rôle grandeur nature knudepunkt knutepunkt kung-fu lacepunk larp le four fantastique murder party mythodea nodal point nordic larp old news orc'idée podcast radio roliste rap review roliste sk2012 solmukohta steampunk stim suisse swiss larp switzerland thomas b. XVIIIèmePeeps be commentin’

- GEESAMAN8 on Deux GN avec du Star Wars dedans, un marathon et de l’oralité

- Steampunk Props Part 3: Gun, Smoke Rings video, Bubbles, a Chandelier and Art by Latranis - Thomas B. on Cheese-eating larper monkeys: the GNiales 2011 recap

- I'm a size 47 media whore and here's what sells online - Thomas B. on And they piss like I cry over unfaithful women

Search

[…] Afroasiatik – a kung-fu hip-hop larp – recap part 1 […]

[…] here for part 1 and part 2. Yes, it’s important to read them […]

[…] Afroasiatik – a kung-fu hip-hop larp – recap part 1, un compte-rendu de GN cinglé signé par Thomas B., GNiste cinglé (mais génial) […]

[…] More photos and details on the design process, on this blog (English) […]

[…] every second. For attendees that asked for a playlist, start with the video links at the end of this blog post, then go to part 2. For those that asked for more workshop videos, design methods etc, please […]